This is a breakdown courtesy of the latest scientific research on how we respond to signals that we “aren’t enough” or are “less than.” It is fascinating how we evolved to care what others think.

This is a follow-up to my posts on criticisms and Jonathan Haidt’s analysis of microaggressions. Haidt believes that we should desensitize ourselves to criticisms and insults and not be a part of the callout culture. I agree with his advice that it is better to learn how to cope with criticism than to shield ourselves from it. However, there are groups of people that are vulnerable to pervasive insults and shaming, like minorities, LBGTQ+, or undesirable others, who may benefit from protection in hopes that they can rise in political and cultural status. This becomes a challenge since many believe it is a fundamental right of freedom of speech to criticize others. If a criticism bears truth, then it is our right to disparage others, especially if they or their attributes are inferior or inadequate. This can be settled by one question. Is our goal in life to be right or to get along with others?

How We Respond to Criticisms and Insults

Criticisms are when we “find fault” in something or someone. Everything else is a variation on the criticism but expressed with various intentions, emotions, subtleties, and body language. It becomes abusive if we want to inflict emotional harm (i), which is a form of emotional abuse. Abusive criticisms can be formed as insults, humiliation, epithets, disparage, ridicule, contempt, mocking, teasing, innuendo, slur, and sarcasm. A stipulation is that the attack must be on our appearance, abilities, character, intelligence, or affiliations. These areas are vulnerable because we do not want to be exposed as “less than” or “not good enough” to some desirable standard. We prefer not to deviate from desirable standards because we may feel shame, hurt feelings, and anger.

Take an insult that Donald Trump has said to Robert Denerio and Mika Brzezinski, “You are a low IQ individual.” This is an abusive criticism, specifically an insult, as it is intended to inflict emotional harm; however, it may not be a criticism in the strict sense. It is criticism if there is truth to it, which lies within the perception of others. Knowing Trump, this insult was likely uttered with contemptuous emotion to enhance its effect. Contempt signals that we are not worthy of consideration since we or our attributes are inferior. What about the insult that those are “shithole countries? Since our place of origin and culture are tied to our identity, then we should be offended. Even though this is not a direct criticism, we can feel shame by identifying with an inferior place or group.

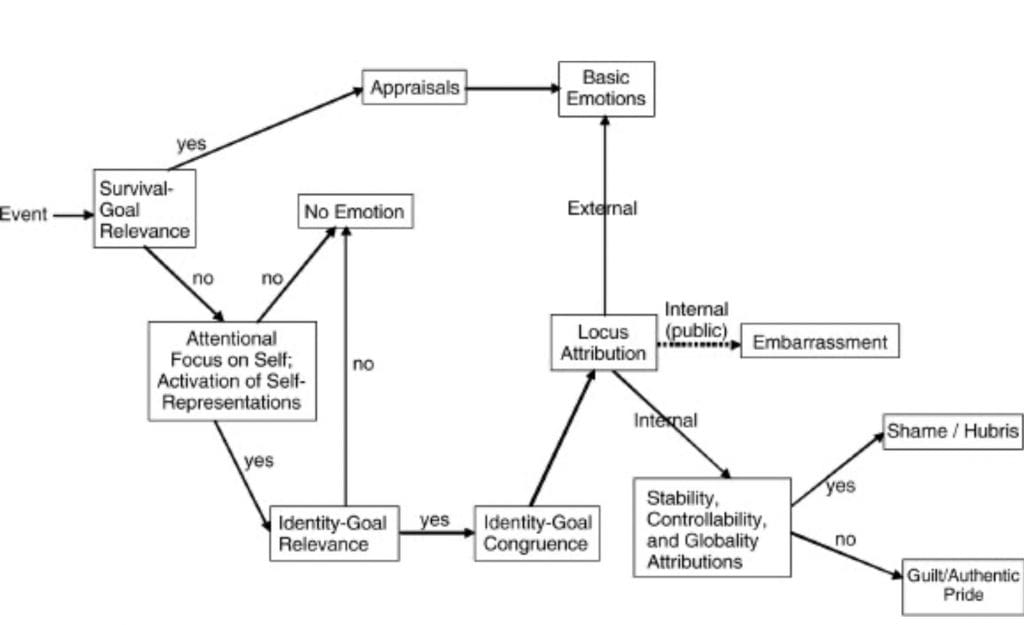

Let us say we made a mistake at work, and someone said that we were “careless and dumb.” This is a clear insult but could also be a legitimate criticism if that is how we are perceived. If we hear something frequently, there may be some truth to it. But how do we process this? Initially, we may not fully process the threat. The brain will realize, however, that it is a threat to our self-worth, and we will feel anger because we externalize the event—that is, it is coming from a source that is not us. Anger is the emotion of self-preservation, and it tells others that we won’t be pushed around. However, responding to a perceived slight with anger is unacceptable at work, and we are aware of this instinctively. The only other option is to attribute the slight to internal causes.

If we attribute our failures to our abilities or intelligence, things that are beyond our control and cannot be changed, we will feel shame. If we attribute it to not trying hard enough or to things within our control, then we feel guilty. That is not all. If we process this as the person no longer holds us in high esteem or values us, then we can feel hurt feelings. Narcissists, on the other hand, deflect criticism with a hubristic sense of pride.

- Does the criticism threaten who I am supposed to be— e.g., a capable, intelligent, and attractive person?

- If so, then proceed to step 2. If no, then stop.

- Is the threat internal (caused by me) or external (not caused by me)?

- If we attribute the threat to someone else, then we can display anger. Go to 4.

- If we internalize the danger, which is an unconscious process, then go to 3.

- Is the threat something that is out of my control or within my control (ii)?

- If it is out of our control, then we feel shame. If it is within our control, then we feel guilt.

- Do we imagine ourselves as the criticism portrays us or ruminate over our feelings of being mistreated?

- If so, this can lead to anger or rage. We can have the thoughts of “Who do they think they are?” and retaliate.

Emotion Determination [1]

What if it is generally believed that we are ugly, stupid, inadequate, or undesirable? People, of course, fall on a continuum within these categories, but we tend to categorize and stereotype them. We are either in or out of a category. He is attractive. He is not attractive. He is smart. He is not smart. There must be some threshold within the continuum that allows us to make these black-or-white appraisals. Therapists, however, warn of global or black-and-white words because they can induce the emotion of shame. Why do they induce shame? If it is us that global words necessarily imply, then we are forced to make a worldwide attribution and feel shame as a consequence. If we instead say that certain aspects of us are ugly or dumb, then we may not trigger shame. It is the extent to which the internal attribution is stable, controllable, and global. And “the degree to which shame becomes spread to a global sense of self depends on the meaning and values of the roles and attributes that are deemed important for self-definition and identity [1]”.

References

[1] The Self-Conscious Emotions. Tracy, Jessica.